Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings at 50 (me, not it)

A young Tolkien, just after the war

A

friend of mine recently sent me this

article by Melissa Brinks at Ranker about uncovering Tolkien’s failings as

a man through evidence in his works. It isn't really worth reading, a sort of execrable

piece of chickenpoop clickbait with a great many of the usual accusations leveled

against works of greatness such as those of Mister Tolkien. Excusing most of

the fallacious arguments to a gross lack of knowledge about the actual text (it

seems the author is far more familiar with Peter Jackson's inferior

LOTR than Tolkien’s masterful Lord of the Rings) there are one or two

things which seemed to need some answer. For instance, the author accuses Tolkien

of misogyny, bigotry, and racism. This really gets under my skin. Not only do I

dislike the modern penchant for judging past works by current mores, these

accusations simply are not true of the author.

Tolkien's watercolor of the Shire

As

to the misogyny, Brinks quotes one of Tolkien’s more beautiful letters to his

son urging Christopher to take care of the women in his life and treat them with

the greatest respect he possibly can. Brinks quotes a portion of one letter out

of context which seems damning to the professor but it is worth reading the letter (which, we

must remember, was meant as a caution for his wavering libidinous son) in full

to understand his meaning. Here is the

portion, in context, which Brinks uses as evidence of Tolkien’s misogyny:

Women really have

not much part in all this (the guiding nature of chivalry and romance), though

they may use the language of romantic love, since it is so entwined in all our

idioms. The sexual impulse makes women (naturally when unspoiled more

unselfish) very sympathetic and understanding, or specially desirous of being

so (or seeming so), and very ready to enter into all the interests, as far as

they can, from ties to religion, of the young man they are attracted to. No

intent necessarily to deceive: sheer instinct: the servient, helpmeet instinct,

generously warmed by desire and young blood. Under this impulse they can in

fact often achieve very remarkable insight and understanding, even of things

otherwise outside their natural range: for it is their gift to be receptive,

stimulated, fertilized (in many other matters than the physical) by the male.

Every teacher knows that. How quickly an intelligent woman can be taught, grasp

his ideas, see his point – and how (with rare exceptions) they can go no

further, when they leave his hand, or when they cease to take a personal interest

in him. But this is their natural avenue to love. Before the young

woman knows where she is (and while the romantic young man, when he exists, is

still sighing) she may actually 'fall in love'. Which for her, an unspoiled

natural young woman, means that she wants to become the mother of the young

man's children, even if that desire is by no means clear to her or explicit.

And then things are going to happen: and they may be very painful and harmful,

if things go wrong. Particularly if the young man only wanted a temporary

guiding star and divinity (until he hitches his waggon to a brighter one), and

was merely enjoying the flattery of sympathy nicely seasoned with a titillation

of sex – all quite innocent, of course, and worlds away from

'seduction'.

43 From a letter

to Michael Tolkien 6-8 March 1941

Tolkien

is not misogynistic in his writing, but his age thought of women as members of

society to be protected and honored. The fact that this author accuses him of misogyny

speaks more about our loss of that sense then of Tolkien’s supposed dislike of

women. Tolkien in his own correspondence with women is always courteous, kind,

and exhibits a respect of their intellect and questions which indicate the

attitude of a refined and noble human being.

In

responding to Naomi Mitchison, a prolific novelist and memoirist who read

proofs of Lord of the Rings he wrote

It has been both

rude and ungrateful of me not to have acknowledged, or to have thanked you for

past letters, gifts, and remembrances – all the more so, since your interest

has, in fact, been a great comfort to me, and encouragement in the despondency

that not unnaturally accompanies the labours of actually publishing such a work

as The Lord of the Rings. But it is

most unfortunate that this has coincided with a period of exceptionally heavy

labours and duties in other functions, so that I have been at times almost

distracted. I will try and answer your

questions. I may say that they are very welcome.

After

a long letter Tolkien concludes by noting her “delightful and encouraging

interest” and saying that he is “deeply grateful for it.” His words indicate an obvious delight with

the depth of her interest in and knowledge of the secondary world he was

creating. Finally, the fact that the majority of his characters are male speaks

to his own military experience of the time, not to misogyny.

Tolkien with classmates

Tolkien, fourth from left in the middle row, stands for inspection with the new Cadet Corps at King Edward’s School, Birmingham, on 4 April 1907

One wonders if Brinks

would suggest a revision of other great works such as Lord of the Flies or Beowulf

to incorporate more badass female figures. Tolkien was more aware of the grace

and beauty of Wealtheow than of the kick butt and take names heroine of our

current Marvel Universe. Brinks’

suggestion that he treated the love of his life, his wife, whom he married despite everyone’s

advice and the possibility of his own ruin (she was the daughter of his

landlord) is not even a comment worthy of address.

Tolkien's lovely bride, Edith

The Tolkiens together in life and in death

Concerning

bigotry, again Tolkien was not indicating that lower class people we're not as

important as upper class people. Quite the opposite. His experience on the

battlefields of Europe, like the experience of so many young men of his era, was

a leveling experience between upper class and lower class not a calcification of

the various strata of society from the 19th century. Like Lord Peter Wimsey and

his man Bunter in Dorothy Sayers’ novels, Frodo sees Sam not just as an equal but

really as a better man than he is. The alleged bigotry towards other religions such

as Judaism is an outright laughable accusation. I have long thought that Tolkien

based his races on different religious groups of his day. The high elves seem

to be the Anglican church and the low elves seem to be the low Anglican church;

the dwarves seem to mirror the Jewish communities in England; the men and the

hobbits seem to be Catholics; even the men of Harad seem to be the Muslim community

of the Ottoman Empire. But Tolkien’s

world of Middle Earth was an alternate world – intentionally so. Though like any author he draws on his own

experience and models his work upon it, he is not making an identity as the

author of this article so fatuously suggests.

Even were he to do so, the dwarves are extremely impressive as a race in

all his novels (Silmarillion to Hobbit to Lord of the Rings to Lost Tales). Even the most threatening group of the men of

Haradwaith are misguided by their seducer, Sauron. The enemy of orcs are themselves not evil by nature,

but elves tortured to the point of becoming destructive. Tolkien’s sense of evil is far more complex

than Brinks gives credit. He always

seemed to see evil as a torture, imprisonment, misguided thing – not as the “ultimate

evil” of our video game age (which, tangentially, is another reason for my

dislike of Jackson’s LOTR when compared to Tolkien’s masterpiece).

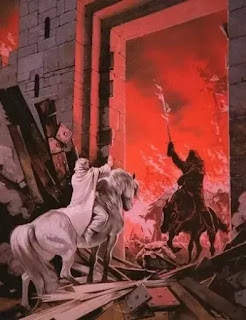

Tolkien's watercolor of Barad-dur

Thus,

even the accusation of racism seems completely inane. Tolkien was no racist. He had a deep love for Norse mythology,

Germanic tradition, English history, and somewhat the French, but he was born

in South Africa and knew the traditions of the Zulu people. He praised the learning of the 14th century

Muslim scholars. He even wrote a protest

note to Mr. Adolf Morgothed Hitler praising the Jewish people as “that gifted

people”!

Thank you for your

letter ... I regret that I am not clear as to what you intend by arisch. I

am not of Aryan extraction: that is Indo-Iranian; as far as I am

aware none of my ancestors spoke Hindustani, Persian, Gypsy, or any related

dialects. But if I am to understand that you are enquiring whether I am

of Jewish origin, I can only reply that I regret that I appear to

have no ancestors of that gifted people.

— Tolkien, The

Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien, #30

The

chance that professor Tolkien was any more racist than anyone else of his era

is miniscule and the accusation that evil characters in the movie were “made

more black” is risible. Tolkien well

knew the difference between men and women with brown or dark skin and the

blackness of Grendel, Ungoliant, and Baphomet.

If the accusation of racism is to be tossed about perhaps more should be

slung at Peter Jackson who overused the imagery and played the “evil” card far

too freely.

This is not how orcs are made!

The

article raised my hackles and got up my Tookish fighting blood, it is true, but

I must thank both the article and my friend for sending it my way. I had of late, wherefore I know not, lost

most of my mirth, forgone most customs of exercises, and indeed it went so

heavily with me that I even failed to lift a glass on September 22nd to my two

favorite Hobbits (you know who you are).

When I grew heated over this silly little bit of tripe wrapped in scheissvertisements

I decided it was time to pick up the professor’s great work again and read it

to my young daughter. Soon my older

children wanted to listen too, and we were soon reading once again the work I

remember my father reading to me from childhood. Frodo, Sam and Pippin have just met Merry at

the Buckleberry Ferry after spending some time with Farmer Maggot, and I am

remembering how, once again, my father was right – this work is one of the few

works of the 20th century about hope.

This

This

and certainly this (no female characters my ax!)

the Shadow is but a passing thing

If

you haven’t yet listened to professor Dr. Helen Lasseter Freeh’s interview on this work, I

suggest you listen to her (disclosure: we are of one blood, she and I).

One of the

things she points out is that Tolkien’s work is filled with joy and hope

(another reason for me to dislike LOTR).

There is hope in the singing, the rescue by the elves, the landscape,

the description of flowers and trees, the conversation with Maggot about mushrooms,

the humor of Grip, Wolf and Fang charging the hobbits, there is joy in the

travel with companions even when it is dogged by black riders, there is joy in

the party of Bilbo’s 111th and in the saving power of Gandalf allowing Bilbo to

freely give up the ring.

Frodo and Gandalf by Alan Lee

There

is even hope and joy in the dark conversation between Frodo and Gandalf about

the ring in chapter 2. Yet it was here

that I noticed a few very startling things I had not previously seen (that’s

the beauty of a great work – it doesn’t change but we do and notice new things

in it as we change!). First, the race of

Hobbits is the ordinary human race – the average Joe (or Tommy) who simply

wants his ballgame and his beer and his children to make it through school

okay. They are not happy singing midgets

like the munchkins or like Darby O’Gill’s little people.

This would NOT be Hobbits

Nor would this

and NO

The glory of the Shire is that it is so ordinary,

not that it is some rural paradise filled with maniacal partying and singing denizens

of Cymru as yet untainted by industrialism (another reason for me to dislike

LOTR). They are people who don’t want

big ideas or grand adventures; “We don’t want any adventures here,” said Bilbo,

“Good day.” People who are so far from being mariners on the deep waters of the

human spirit that they are scared even of small streams and suspicious of

anyone who messes about with boats “and other queer things.” Such people are not helpful in the great

struggle with the horror of the enemy – in fact they can be a hindrance, even

treacherously so. Nor are they children innocently

enjoying the world in the newness of springtime (as Ralph Bakshi and Peter Jackson

both suggest – and if you haven’t yet seen the Bakshi overdub you must go enjoy

some ribald humor on YouTube). Farmer

Cotton, the Gaffer, Bullroarer, Belladonna Took, Lobelia S-B and even the young

adventurers all suggest that these are seasoned adults, not babes.

So

why are they worth preserving? What is

it about the Shire that makes Frodo want to protect it? It isn’t just the trees and fields (as is

suggested in LOTR). Nor is it just the

drinking and dancing on tables (rrrrghh, Mr. Jackson!). Yet there seems something in the nature of

the ordinary which Tolkien suggests must be the focus of the heroic – something

which needs protecting even though it doesn’t know that it does. Nowhere in his book does he suggest that the

elvish society needs protecting; quite the opposite. We know from the outset that elvish society

is doomed to perish; Elrond says so, Galadriel says so, even Glorion says so. Frodo meets elves fleeing Middle Earth. The elves throw themselves into battle

knowing they will fail. Nor does the preservation

of dwarvish society get much emphasis, though there is mention of battle in the

North near Lonely Mountain. Never does Gimli

or any other dwarf make the claim that they are fighting to preserve dwarvish

culture. Even the men of Middle Earth

frequently seem to suggest that they are fighting to hold back the darkness,

not to preserve the beauty and greatness of Minas Tirith or of Rohirrim. Even the attempt to preserve the White City

becomes the downfall of great men like Boromir.

Only the Shire seems to want or need preserving in the book. Perhaps Tolkien is suggesting that this is

the core of our own race, the ordinary, peace-loving, shallow thinking race of

human/hobbits that just want to be left alone. Could it be that this is worth preserving more

than all the Chartres and Palmyras and Reichstags of civilization?

The

other aspect to the Hobbit race in Tolkien’s works is their tremendous resilience. I noticed this time around how intimately

tied were Frodo and Gollum – far more than Bilbo and Gollum in The Hobbit. From Chapter 2 onward (in which Gandalf and

Frodo discuss the history of the ring) we already know Gollum’s real name,

Smeagol, his back story, his years of loneliness and suffering with the ring,

and his recent capture in Mordor and torture by Sauron. Frodo suggests that it was “a pity Bilbo didn’t

kill him when he had the chance” to which Gandalf responds “you have not seen

him.” Indeed, the wizard adds, “it was

pity that stayed his hand” and thankfully for Bilbo pity was how he began his

possession of the ring of power. From

the outset of the journey Frodo is thinking about not only the ring, but Gollum

and how he, Frodo, may end up like Gollum.

At first he denies that this might be so, even growing heated at the

suggestion that Gollum may have been related to Hobbits. But Gandalf responds that the evidence, the

riddles, the resilience to the ring, the cultural identity, all suggest the

opposite.

Herein

lies a crucial element of Tolkien’s genius.

It is one thing to hate our enemies, to make aliens and monsters out of

them so that we might crush them, as Niell Fergusson suggests so many did

during the Great War. But this is lazy,

slipshod thinking and pusillanimity of spirit.

The truly heroic action of the heart is to recognize that our enemy is

the same as we are; that in different circumstances we not only might do but indeed

probably would do the same thing as they.

The recent heroic actions by Brandt Jean toward Amber Guyger illustrated

that indeed, our enemies suffer just as we do, and that forgiveness is the only

possible route to our own salvation.

Indeed, such recognition must accept that the greatest horror conceivable

is not beyond our own power. Frodo

becomes the Dark Lord at the end of the novel (spoiler alert) and not in some

cinematic, CGI-gasm of fire and action, but in a rather pathetic statement of

self-delusion that happens unbeknownst to the rest of Middle Earth. Something more like Marvin the Martian and

his p38 space modulator or Plankton trying to rule the world than Elijah Wood’s

overacting (another reason to dislike LOTR).

overacting

better

better still

probably best

In the end, the ring so corrupts Frodo that he thinks he is something

great, he is delusional and loses himself.

Frodo fails and dies (spiritually) at the end. Or, perhaps to be fair, he is so close to failure

that he almost dies. Ultimately, he is

saved… by Gollum. The earlier kindness

and mercy shown to Gollum/Smeagol certainly contributed to the salvation on

Mount Orodruin, but even that does not assure the salvation. The only thing that seems to is an Actus Dei,

an act of God, through the person of Gollum who bites off the ring finger and

falls into the fire. Gollum, one could

say, is damned, Frodo is saved. But

Gollum and Frodo, Tolkien intimates, are one and the same – bound together by

the ring which “brings them all and in the darkness binds them”. Even after the salvation by the eagles and

the return home, Frodo is not the same person and eventually wishes to pass

with Bilbo into the Grey Heavens (Avalon) of eternal life, leaving behind the

grieved by joyful Sam, who might after all be the main character of the book.

my favorite photograph of the good professor

Finally,

it dawned on me with some remarkable joy that the novel holds a special place

for me this year. Allow me to RambleOn. When Frodo sets off on his journey

he is 50 years old. In Hobbit years that’s

about 20 or so, but the fact that he literally is 50 struck a chord. Frodo is in love, at the beginning, with the

normalcy and beauty of the Shire, but he also is feeling a bit pudgy, somewhat

bored, and as though nothing in his life is ever going to be really exciting

again. He is beyond those dangerous

years of his tweens (the 20s) and on the road to being “respectable” (visavis –

sedentary). When the ring comes to him

and the adventure begins he finds himself not wanting to accept the

responsibility and not wanting to leave the shire. But he does for the sake of protecting

others. In so doing he finds that he faces

tremendous peril, sorrow and loss (Frodo doesn’t know, after all, that Gandalf

is alive and thinks him dead twice in the novel – once until Rivendell and again

after the last battle and his recuperation in Minas Tirith), but he saves all of

Middle Earth and is honored ever after for his sacrifice. Being myself on the near approach to the event

horizon of 50 I sympathize deeply with my fellow hobbit and as I sit here

shoeless I intend to raise a glass after typing this. Here’s to all those small, seemingly insignificant

fellow lovers of good beer, song, laughter, mushrooms and the last light of the

setting sun shining on the keyhole. May

the hair on our toes never fall out!

Comments

Post a Comment