Comic Books and the Word

Recently a colleague suggested that the medium of comic books is inferior to the medium of the paragraph and novel or short story. I am not sure that I agree. The medium of writing is, itself, an invented medium. We are taught to translate the figures we see on a page into words in our head that signify meaning. Does this meaning suffer from being initiated in a thought or word bubble? or in text next to pictures? Is the meaning more powerful in a lengthy sentence or paragraph or novel? I don't know.

Historically speaking the novel itself was not invented until roughly the 17th century in Europe. Prior to that the play, the poem, the chanson or song were the major sources of written meaning. Libellas (little books), pamphlets, leaflets all were popular after the printing press. Even the divine word contained in the Bible was itself a collection of poems and some poetically narrative prose. Most popular were Chivalric Romances by Cretien, or Malory, or von Eschenbach, written either in poetry or in short narrative prose. Before the medieval era the oral traditions of poetry - before that the Romans and Greeks writing in poetic drama or prosaic political thought. The point being that the paragraph and the modern form of novels and novellas are quite recent. Also, the written word seems to have always been accompanied by some other medium - song, drama, pictures or other embellishments. Why would the "addition" of pictures and words in bubbles alter that?

I am indebted to an art historian colleague of mine who pointed out that Japanese artists as early as Medieval Japan would decorate the armor of samurai warriors with small pictures depicting (depictures?) the deeds of great warriors. This, she noted, was the origin of comic book manga in the Orient.

Yet we have extensive record that illustration frequently accompanied works as magnificent as the Book of Kells,

or as comical and lowbrow as the doodlings of monks in the margins of their texts.

Vikings doodled and graffitied the woodwork of Hagia Sophia whilst waiting for their slave trades to conclude. Romans drew funny pictures of the Picts or of their commanding officers and decorated the walls of their buildings with pictures both lurid & divine. Greeks illustrated the walls of their cities with various illustrations from the marvelous to the obscene.

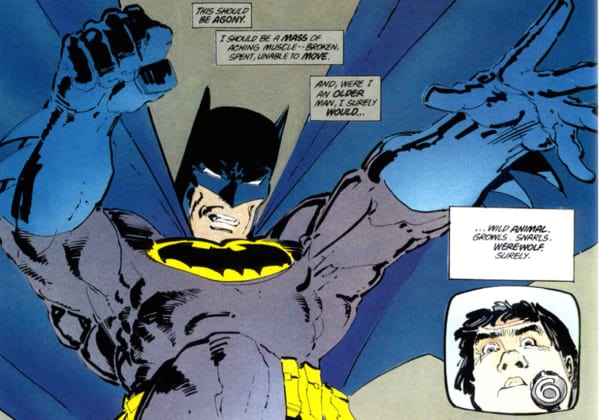

So does the meaning suffer when the word is accompanied by the visual? Not necessarily. There have been great examples of artists combining the word with the visual in a manner more effective than would be the word alone. Coming immediately to mind are

Frank Miller : "The Dark Knight Returns"

Sean Murphy : "Batman White Knight"

P. Craig Russell : "The Magic Flute"

Alan Moore : "The Swamp Thing"

Jeff Smith : "Bone"

Kyle Baker : "Through the Looking Glass"

Bill Sienkiewicz : "The Shadow"

Jon Byrne : "Dark Phoenix"

In each of these examples the word is not hindered but enhanced by the accompanying artwork. What is true is that any translation from one medium to another (page to music, book to film, stage to screen) ultimately has to be an interpretation because it effects us in a different manner. So the great epic, for instance, of Dante's "Inferno" can be translated to the comic page (or the stage, or the screen) - but not entirely successfully. The original poem in terza rima is really the only perfect way to access what Dante had to say. But, to be honest, the poem needs to be read in Italian (and Medieval Italian at that) because even a translation to English changes the nature of the poem. Compare Dorothy L. Sayers' translation to John Ciardi's and this becomes apparent.

Since I can't read Italian (not even Medieval) I've had to settle for a good translation in English. If someone couldn't read complex English poetry, would their settling for a well done comic book version be alright? Certainly; but the knowledge that they were settling for a translated and somewhat inferior version must be acknowledged and hopefully goad them into striving toward the original.

Reading a piece of prose or poetry takes a well-trained mind. It is difficult work. Certainly every time I hold up a work such as "The Iliad" or Plato's "Republic" or Dicken's "Tale of Two Cities" the first reaction from students is "Are we really going to read all that?" (as though reading fifty pages of words is somehow more difficult than reading five pages of words). A culture trained to read read words, a literate culture, accesses meaning through words primarily. What we seem to be experiencing in our own generation is a shift from literacy to illiteracy. We are becoming a post literate culture; relying more on images than on words. Or perhaps more accurately, we are coming to rely more on one form of images rather than another (since words are themselves images). The images we use, the medium we employ, is always trying to convey a meaning. Yet, the medium we use to express that idea has meaning itself. As MacLuhan quipped, "the medium is the message." Comics aren't inferior - but they are different. Understanding and working with that difference is crucial to our flourishing in meaning.

Comments

Post a Comment